Who, What, When, Where, and Why: WHAT, part two

(The fourth post in a five-week, five-subject series that summarizes an entire semester of Journalism 101.)

Let’s assume you have a killer story. You might be an organic writer who dumps into the computer, returning to pummel the story until it makes sense to the rest of the world. Or you might be a hyper-organized type who outlines, sub-outlines, then creates an oh-so-neat first draft. Regardless of how you get there, I’d like to share six checks-and-balances I use to prepare a manuscript for submission

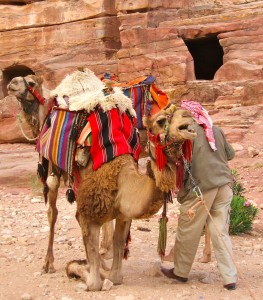

Ensure each scene has an abundance of senses, then tease them out. Some senses are easy: sight, sound, and smell. Touch and taste are often overlooked. The best writers go further, giving readers a feel for characters. For instance, instead of writing, “she hid behind the camel,” do something like, “she ducked close to the camel, her shoulder brushing its side as she peeked around its haunch.” The first example tells you she’s hiding, the second gives you an idea of her body language, stress, and danger.

sight, sound, and smell. Touch and taste are often overlooked. The best writers go further, giving readers a feel for characters. For instance, instead of writing, “she hid behind the camel,” do something like, “she ducked close to the camel, her shoulder brushing its side as she peeked around its haunch.” The first example tells you she’s hiding, the second gives you an idea of her body language, stress, and danger.

Be weird. Nothing’s more boring than normal. Sure, every manuscript has to have normalcy to be believable, but give readers a sense of character and plot idiosyncrasies. These elements bring reality to your writing table. For instance, I have a character with a red buzz cut, which he dyes. Although that’s different, what makes him memorable is that he’s an old theologian. Now that’s strange.

Find balance between your target market and characters. If you know your market, you know their vocabulary. Don’t write above their heads, or below their I.Q. Match characters’ roles with appropriate vocabulary. A woman with a doctoral degree won’t use “ain’t” any more often than a Bedouin says “balderdash.”

Get ugly. My mentor looks for conflict in my work, telling me it drives a story. She’s right. By the time we’re adults, we know better than “happily ever after.” Write truth. Sometimes it’s ugly.

Engage emotions. I covered character psyche earlier in the series, but you can share joy and grief with readers only if you know your characters well. Readers want to relate, stay in the story, and care about people who populate it. They can do this only if you share emotions coloring life. And don’t avoid grief. It’s hard to live through, and write about. But the redemption that follows is the readers’ pay off.

Engage emotions. I covered character psyche earlier in the series, but you can share joy and grief with readers only if you know your characters well. Readers want to relate, stay in the story, and care about people who populate it. They can do this only if you share emotions coloring life. And don’t avoid grief. It’s hard to live through, and write about. But the redemption that follows is the readers’ pay off.

Use only material that drives your story. This is the hardest. Learn to identify the difference in a well-written, lovely, exciting scene that is truly irrelevant to moving your story forward, and one that propels the story to keep your reader engaged. This discernment marks a pro, and I urge you to be utterly ruthless in your editing. I still struggle…

Do you have checks and balances for your work? I’d love to hear about them.